The Lebanese resistance’s stance on arms is not shaped solely by changing events but by a deliberate and unwavering decision from its leadership. Over recent months, Hezbollah’s position has become increasingly clear: disarmament is not, and will not be, up for discussion.

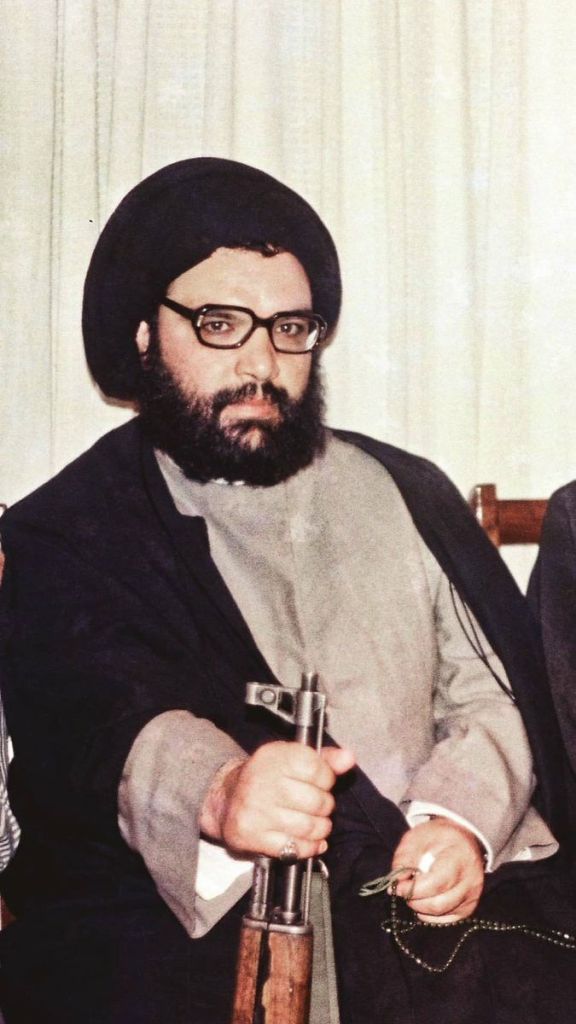

This position does not stem from pride or obstinacy, as critics claim, but reflects a deeper transformation that demands explanation, not justification. A collective awareness has emerged within Hezbollah, its environment, and much of its support base- primarily among Shiites, and increasingly among others- that weapons are not merely for confronting Israeli occupation, but for facing what Hezbollah Secretary-General Sheikh Naim Qassem has described as an “existential threat.”

Any debate at this stage is exceptionally difficult, not just because resistance remains a highly sensitive issue, but because the entanglement of personal, sectarian, regional, national, Arab, and Islamic identities has produced a reality too complex to be untangled by a theorist lounging by a quiet lake on the far side of the world. What is unfolding in the Levant today defies the conventional political science frameworks. A growing sense of minority anxiety, now felt by at least a third of the region’s population, has intensified sharply since the fall of Baathist rule in Syria, following the earlier US-led toppling of Baathist rule in Iraq.

This context requires explanation, even if such explanation carries traces of justification. Sheikh Qassem’s remarks reflect a straightforward reality: Shiites in Lebanon and the region have gained political and economic inclusion as a direct result of their increasing involvement in pivotal regional events. The resistance, above all, has been the driver of this transformation.

Even under Imam Musa al-Sadr- the influential Shiite cleric and political leader who mobilized Lebanon’s Shiites in the 1960s and 70s- this shift in political standing would not have occurred without explicitly calling for Shiite participation in resisting occupation. At the time, many Shiite social forces engaged in the struggle for liberation through political and intellectual frameworks that transcend sectarian identity.

Today, Sheikh Qassem affirms that Lebanese Shiites, as Hezbollah’s primary base and as the resistance’s emotional, social, and economic anchor, perceive a profound existential threat. The Israeli occupation, which they have confronted with resolve since 1978, continues to seek revenge through violence and siege. At the same time, Arab regimes that see Hezbollah as a threat to their stability pursue their own campaigns to target the resistance in Lebanon.

Moreover, the participation of Lebanese and Iraqi Shiites in defending Syria further fueled sectarian hostility, portraying them as partners of the Assad regime against its opposition, many of whom are now in power. This is compounded by Iran’s role in the region: Lebanese Shiites, having significantly benefited from Tehran’s exceptional support, have become entwined in Iran’s strategic posture. As a result, Iran’s enemies have increasingly come to regard Lebanese Shiites as their own adversaries, and the reverse is also true.

These converging threats shape the political foundation of Sheikh Qassem’s statement: the resistance will not abandon its weapons. Hezbollah’s commitment has been further solidified by the ongoing conflict in Syria, where the state has yet to reclaim full sovereignty. Armed groups aligned with de facto Syrian president Ahmad al-Sharaa operate independently of state institutions. Whether described as Islamist factions or Bedouin and Arab clans, these groups represent the sectarian-social base of the current Syrian regime.

When al-Sharaa described the clashes in Suwayda as a conflict “between kin from the Bedouins and outlaw gangs,” he was effectively granting citizenship to one side, and denying it to the other. He is fully aware that these factions do not operate under his command, nor do they rely on the state for arms or funding. Instead, they are autonomous political and social entities that regard the Damascus Authority as their representative, unlike some segments in Suwayda, who mistakenly believe that protection is an end in itself, thereby opening the door to legitimizing the protector’s identity.

Relying on the Israeli occupation to confront Damascus is total surrender. Tel Aviv views such actors as disposable tools, just as it does with most Druze in occupied Palestine, who continue to suffer from the systematic racial discrimination that lies at the core of the Israeli entity’s very structure.

Given the realities in Suwayda and the unresolved situation on Syria’s coast, Hezbollah, anchored in a vast social base with deep extensions across Syria, Iraq, and beyond, will not abandon its sources of strength or allow itself to become the next target. Holding onto its arms is not a desire for war, but a refusal to seek protection from forces hostile to Arabs and their collective interests. In this context, disarmament would be reckless; ultimately, a betrayal.

That said, it is worth warning those with influence among Lebanon’s Shiites against relying too heavily on minority anxiety as a basis for preserving the resistance and its arms. One of late Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri’s major political mistakes was reducing Lebanon’s Sunnis from a central force within the broader Islamic world to a mere sectarian community. Hezbollah, by contrast, elevated Lebanon’s Shiites from a historically marginalized sect to a people bearing the nation’s mission in its confrontation with a colonial enemy led by the zionist entity.

Ultimately, the aim of explaining Sheikh Qassem’s position is to foster a better understanding of Hezbollah’s stance and to encourage more serious engagement with the weapons file going forward. But explanation must not obscure a fundamental truth: resistance to colonialism is a cause in itself and must not be diluted by other agendas; otherwise, we might find ourselves in a time where core priorities are lost.

Al Akhbar report

Leave a comment