For the seventh year in a row, the Syrian government and the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration are competing to buy wheat from local farmers, as both sides scramble to secure enough grain to meet the country’s rising demand for bread. The race comes amid stark warnings from the United Nations that Syria is facing its worst wheat harvest in six decades; a collapse that could force a sharp increase in imports to offset the severe shortfall caused by this year’s extreme drought.

Although the fall of the former Assad regime allowed the new government to consolidate power across much of the country, unifying former regime-held areas with opposition strongholds like Idlib and parts of rural Aleppo, Syria’s agricultural crisis only deepened. Relentless drought shattered hopes of recovery, hitting vital crops such as wheat, barley, and legumes.

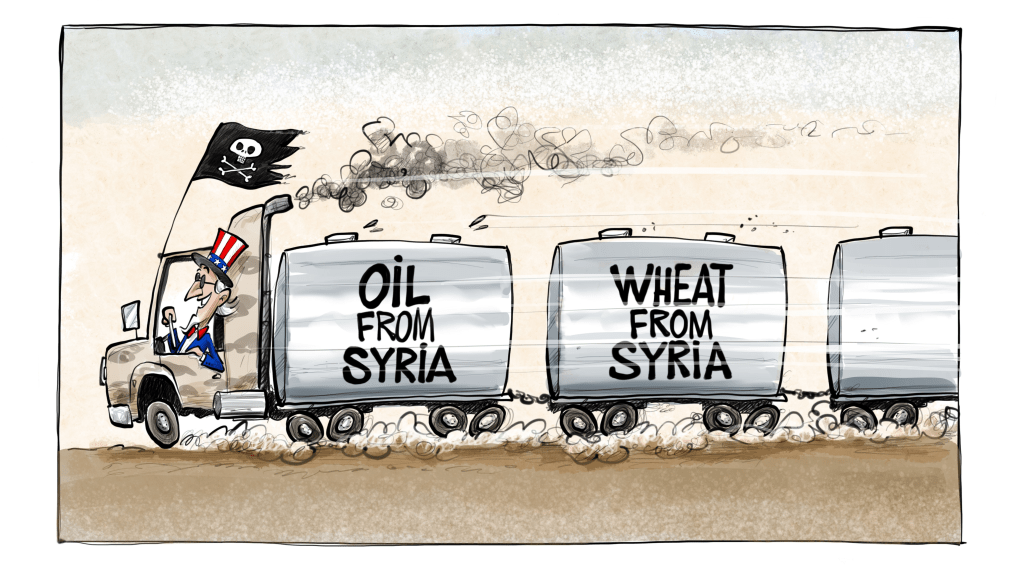

The Kurdish Autonomous Administration continues to control northeastern Syria, fueling competition over the limited wheat supply. With thousands of displaced people, both from within the country and abroad, returning to their homes, domestic demand for wheat surged from previous years.

This year, however, the competition has been noticeably less intense. A prolonged drought destroyed most rain-fed farmland and severely affected even irrigated areas, as rainfall declined and rivers and wells dried up. Hopes for even a modest harvest have been largely abandoned. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recently warned that around 2.5 million hectares of wheat fields have been damaged by extreme climate conditions, placing more than 16 million Syrians at risk.

“The severe climate conditions witnessed this season, the worst in nearly 60 years, will compel Syrian authorities to rely more on imports,” said Haya Abu Assaf, assistant FAO representative in Syria. “This will further strain an economy already crippled by 14 years of war.”

The Syrian Agriculture Ministry estimates that wheat production in government-controlled areas will reach only 300,000 to 350,000 tons this year, far below what is needed to meet national demand. Whereas in northeastern Syria, the Autonomous Administration expects no more than 350,000 tons.

A source from the General Grain Establishment told Al-Akhbar: “The total quantities delivered so far to grain collection centers haven’t exceeded 300,000 tons, a very modest amount considering the growing annual demand, especially with displaced populations returning.” He added: “The Syrian government is now reviewing import contracts to cover this year’s shortfall and prevent a bread supply crisis.”

A source within the Autonomous Administration echoed the concern: “Expected wheat volumes this year will not meet local needs for bread and other uses,” adding that “this is the worst season for Hasakah province, which has been Syria’s wheat heartland since the early 1980s.”

He explained that the Administration “may rely on stockpiles from previous years and could consider imports if necessary, or coordinate with Damascus if full political integration is achieved.” He also defended the decision to ban wheat from leaving areas under Autonomous Administration control, saying: “The Administration provided seeds, fertilizers, and subsidized fuel to the farmers, so it has the right to receive their crops.”

Agricultural expert Rajab al-Salama explained that “the repeated droughts in recent years require serious measures to confront them and an end to relying on rain-fed farming as a main source of wheat.” Speaking to Al-Akhbar, he emphasized that “Arab and Western re-engagement with Syria should focus on rebuilding the agricultural sector in ways that mitigate the effects of drought.”

He added, “There is a pressing need to strengthen scientific research, adopt drought-resistant varieties, and expand irrigated farming through the revival of halted infrastructure projects, such as the long-delayed pipeline to bring water from the Tigris River to Hasakah. Such initiatives could significantly improve Syria’s national wheat production.”

Al Akhbar report

Leave a comment